“…I was glad to be alone. The discipline of the dark envelope summoned fresh images from the forest of how real organisms look and act. I needed to concentrate for only a second and they came alive as eidetic images, behind closed eyelids, moving across fallen leaves and decaying humus. I sorted the memories this way and that in hope of stumbling on some pattern not obedient to abstract theory of textbooks. I would have been happy with any pattern. The best of science doesn’t consist of mathematical models and experiments, as textbooks make it seem. Those come later. It springs fresh from a more primitive mode of thought, wherein the hunter’s mind weaves ideas from old facts and fresh metaphors and the scrambled crazy images of things recently seen. To move forward is to concoct new patterns of thought, which in turn dictate the design of the models and experiments. Easy to say, difficult to achieve.”

—Edward O. Wilson, The Diversity of Life

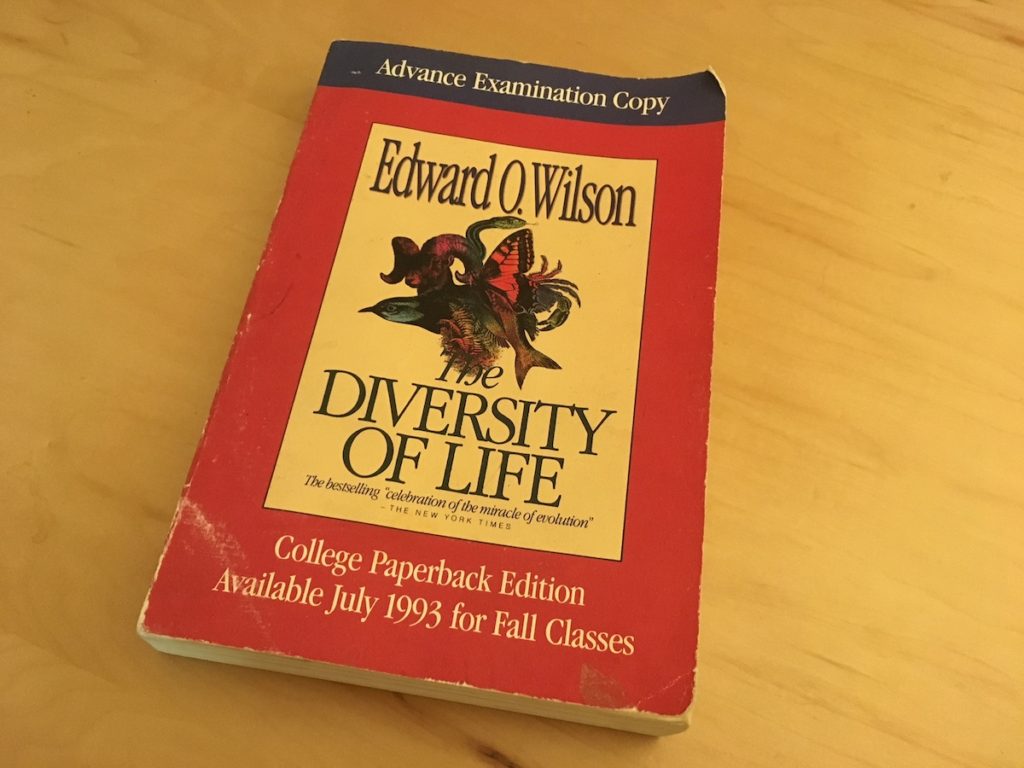

A book-loving friend of mine noticed a small town library we happened to be near was having a book sale. While my friend combed the boxes packed with every imaginable genre of book, I wandered straight to the science section. I pulled out this textbook by Edward O. Wilson, which he describes on the back cover as “three books in one”—a synthesis of what we know concerning biodiversity as an environmental issue, biodiversity studies and conservation biology as part of the natural sciences, and an introduction to evolutionary theory.

I bought the book for a dollar donation to the library, walked outside into the sun, and sat down to read. I was immediately drawn in by E.O. Wilson’s superheroic storytelling ability. I was transported to nighttime in the rain forest somewhere in the Amazon Basin, with the reflection of wolf spider eyes in my headlamp beam. He had me hooked on page 4.

The next day, at a coastal nature center, a young man walked in, spoke briefly with the ranger on duty, and left, returning in a few minutes with this creature on his hand. The ranger said it was a something or other beetle (the name went by too fast for me to catch) and that this beetle was a late bloomer…they live in the ground for seven years, and emerge and mate within 2 weeks. It seemed to be one of the last of the cohort. This particular one was making a loud hissing sound which the ranger told us meant it was disturbed. I managed to take this photo. According to a Washington State University entomology website, the males have large feathery antennae to detect the female pheromones. So I think this is a female. Although maybe I’m just missing the large feathery antennae. I’m emailing the photo to the nature center to see if they can help me identify the gender.

Remember a few weeks ago, I mentioned the AI/AR app, Seek, created by the iNaturalist folks? After searching my brain for the beetle name and failing, I opened up Seek on my iPhone, and selected my beetle on the hand photo, and in less than a second I had this creature’s name with some details about its life cycle and habitat. If you don’t already know (maybe I’m the only one who doesn’t?), meet the Ten-lined June Beetle, Polyphylla decemlineata.

My point…Seek is a really awesome app that is connecting me more deeply with the natural world around me. It’s available for Android and iPhone. Try it with your kids. Take a walk around your neighborhood and see what you discover. Let me know if you do. I’d love to hear what you find and what your kids think of Seek.