I attended an all-day MediaX conference at Stanford University this week with speakers at the leading edge of research into AI, social bots, human-computer interactions, fake news. Presenters and panelists included Mariana Lin—writer behind the voice of Siri, Sam Wineburg—founder and Executive Director of the Stanford History Education Group, Shelby Coffey—vice chair of the Newseum, Esther Wojcicki—founder of the largest high school journalism program in the U.S. and Vice Chair of the Board of Creative Commons, and Byron Reeves—Professor of Communication at Stanford.

The underlying theme across all the talks was about trust and transparency.

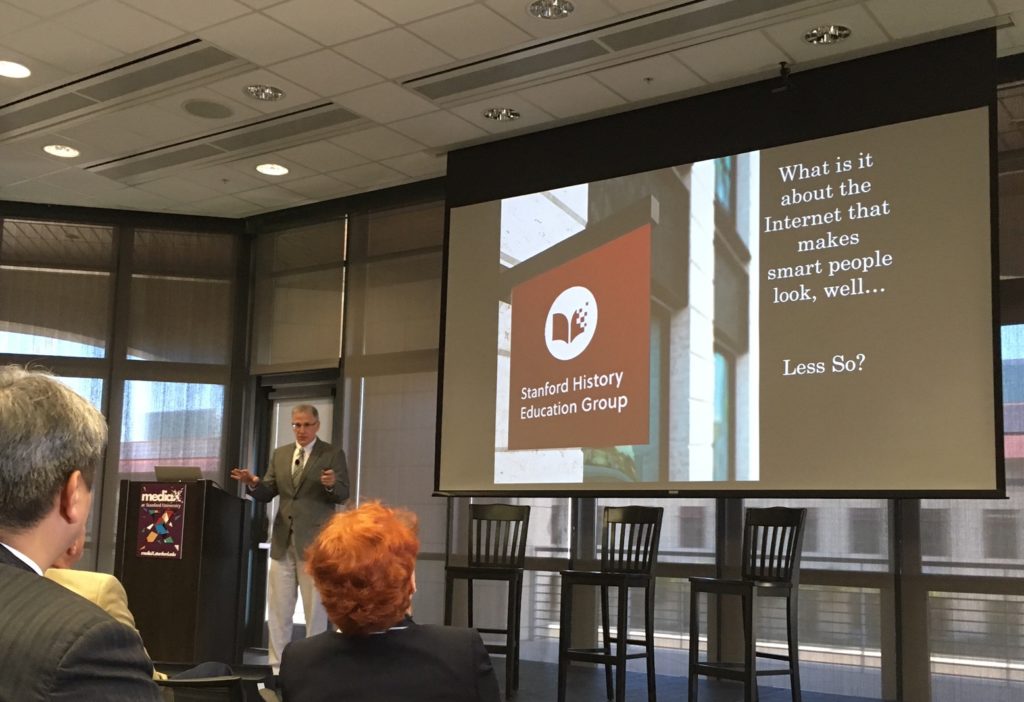

Sam Wineburg, director of the Stanford History Education group (I am a fan—I wrote about SHEG here in December, 2017), discussed SHEG’s research with students on evaluating the accuracy of information online.

From the Executive Summary of the SHEG report:

…we sought to establish a reasonable bar, a level of performance we hoped was within reach of most middle school, high school, and college students. For example, we would hope that middle school students could distinguish an ad from a news story. By high school, we would hope that students reading about gun laws would notice that a chart came from a gun owners’ political action committee. And, in 2016, we would hope college students, who spend hours each day online, would look beyond a .org URL and ask who’s behind a site that presents only one side of a contentious issue. But in every case and at every level, we were taken aback by students’ lack of preparation.

Sam gave the extremely tech-savvy audience an opportunity to demonstrate our skill at evaluating online information. It was pretty clear that not just young people need to level up their information skills. So do adults, this one included.

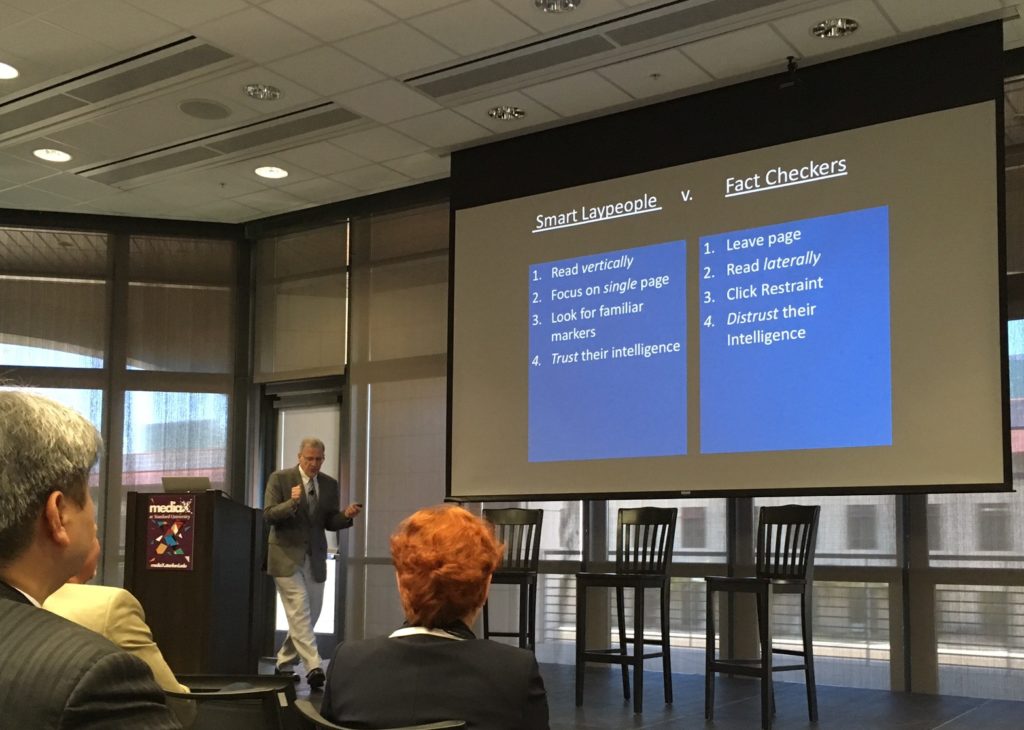

When the SHEG team put historians, Stanford students, and fact checkers to the test, fact checkers left historians and students in the pixel dust. Students, historians and other “smart laypeople” linger on the page they’re evaluating and read from top to bottom. Fact checkers practice lateral scanning—they scan quickly and open several new tabs immediately to research on other sites.

Read this SHEG report to learn what fact checkers do and up your game. Or read this summary of fact checker strategies by Poynter journalist Daniel Funke. Then see the set of assessments SHEG has developed on Civic Online Reasoning to test your own skill at evaluating the validity of online information. If you have tweens and teens, working through the assessments could provide the centerpiece for several weekly tech conversations.

Esther Wojcicki shared another related resource—ESCAPE—an ancronym for remembering six key concepts for evaluating news. Created in collaboration with the Newseum, you can download their excellent set of materials (including the ESCAPE Junk News poster in the photo below) to support you and your family in your quest to become Master Fact Checkers.

Here’s an invitation. Write me (click here to respond) and let me know if you work with any of these materials either by yourself or with your family. I’ll schedule a video call to talk about what you learned. I’d love to hear from you.

What I’m reading: This article, Google’s Got Our Kids, by educator Joanna Petrone, investigates the same themes of Transparency and Trust as the MediaX conference. Thanks to Audrey Watters for the pointer in her Hack Education Weekly Newsletter.

I’m also reading: “Your kids will see Internet Porn. Deal with it. A conversation with Peggy Orenstein by Sarah Fallon.” Short, down-to-earth advice. I read Peggy’s book, Girls & Sex: Navigating the Complicated New Landscape, and heard her speak to a small local bookstore crowd. I appreciate her work tremendously. She’s writing a book about “boys, masculinity, sex, love—and yes, porn.” I hope she finishes it soon. We need it.