Let’s move beyond the fake news meme. Here’s why…

…we sought to establish a reasonable bar, a level of performance we hoped was within reach of most middle school, high school, and college students. For example, we would hope that middle school students could distinguish an ad from a news story. By high school, we would hope that students reading about gun laws would notice that a chart came from a gun owners’ political action committee. And, in 2016, we would hope college students, who spend hours each day online, would look beyond a .org URL and ask who’s behind a site that presents only one side of a contentious issue. But in every case and at every level, we were taken aback by students’ lack of preparation.

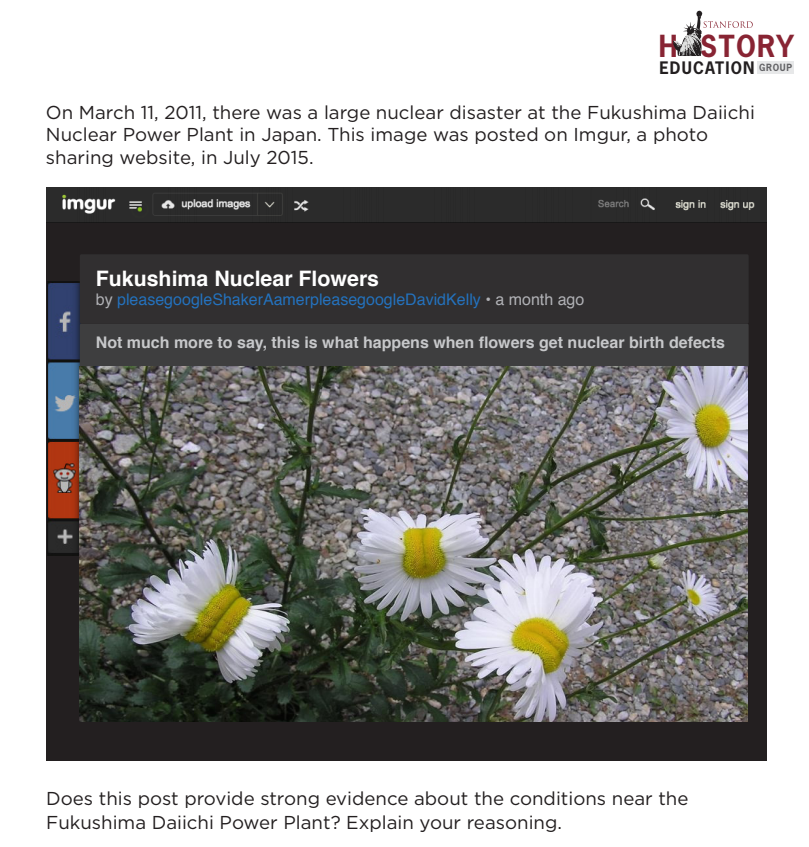

These words are from the opening paragraphs of the Executive Summary of a report by the Stanford History Education Group, “Evaluating Information: The Cornerstone of Civic Online Reasoning.” Between January 2015 and June 2016, the research team prototyped and tested a series of assessments to evaluate middle school, high school, and college students for “civic online reasoning”—”the ability to judge the credibility of information that floods young people’s smartphones, tablets, and computers.” They analyzed 7,804 student responses from across 12 states.

I love these guys—also known as SHEG. They’ve made all their assessments available for download. You will be asked to register (free) and then you can download 20 different assessments. I recommend reading the report which walks you through 3 of the assessments—Homepage Analysis (distinguishing between ads and articles on a homepage), Evaluating Evidence (distinguishing between legitimate and dubious sources), and Claims on Social Media (investigating and evaluating sources of tweets).

If you have a tween or a teen, these would make a great family activity for a Mindful Digital Life conversation. If your children are younger, assess your own critical digital literacy. Work your way through all of them. I guarantee you’ll develop a more critical eye for the digital media you engage with and you’ll become a much more informed guide for your young children as they learn to navigate the info ocean.

The website The Conversation does a great summary of navigation skills for developing critical digital literacy here. Here is a brief excerpt:

1. Get off the website

A traditional approach to educating about these challenges has been conducting “website evaluations” using a checklist. This usually involves judging the reliability of a site based on the information it contains, such as a named author, the publication date, domain name, and so on.

However, this approach underestimates how sophisticated and deceptive the internet has become. Instead of a vertical checklist approach, web users need to interact laterally. That involves getting off the website and searching for other information that can provide clues as to the validity and balance of information it contains. For example, thoroughly researching sites’ authors may reveal their political alignments, if they are funded by another person or organisation with particular agendas, and so on. Accurate answers to such questions will most likely only be found off the website.

2. Use a site’s reference list

Another good strategy is to go straight to the site’s reference list, if one is available. If no reference list is provided, it may well be a good reason to dig deeper.

3. Identify adjectives

Adjectives describe how something feels, looks, sounds and acts. They indicate the tone or mood of the message and suggest to readers how they should respond to the content of the site. A savvy web user can identify adjectives, think critically about how these encourage them to view the content of the site, and then evaluate the compatibility between the message itself and the effect of how the message is communicated.

I encourage you to read the full article.